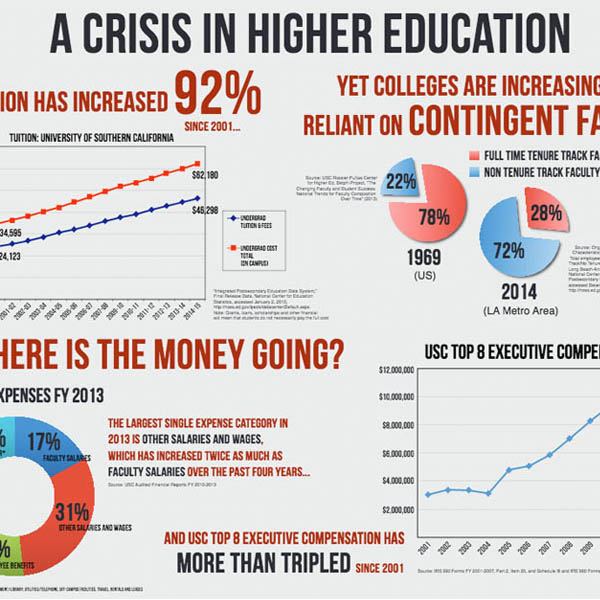

Last week, the Daily Trojan highlighted a very real problem on campus – a sharp increase in high-paying administrative positions that has “substantially outpaced increases in faculty hiring and (student) enrollment”.

This focus on the business of education, rather than student learning, is part of a disturbing trend in higher education that has been well documented at campuses across the country.

That doesn’t make the numbers any less shocking. Again, from the Daily Trojan:

“Amid concern over rising tuition, USC has seen a 305.8 percent increase in hired administrative employees over a 25 year period, while the number of enrolled students has only increased by 66.3 percent, according to a study by the New England Center for Investigative Reporting and the American Institutes for Research which looked at data from 1987 until the 2011-12 academic year.”

This boom in non-academic hiring is certainly troubling, but these percentages only tell us part of the story. As USC hires more and more administrators, they are driving down the cost of instruction by offering our faculty low-paid, temporary employment with no job security and little or no benefits.

In order to fully understand the scope of the problem, it’s necessary to compare faculty salaries to those of USC administrators. Inspired by Laura McKenna’s recent piece in The Atlantic, we’ve pulled together the best data available on the growing income gap between positions devoted to the delivery of higher education, and those positions dedicated to the business of higher education.

As we’ve discussed previously, the majority of USC faculty are hired on temporary, semester-to-semester or year-to-year contracts. These faculty – often referred to as adjunct or contingent faculty – comprise 69%¹ of our university’s educational workforce.

Contingent faculty teach the majority of classes on campus, but despite their critical role, many are barely making ends meet. A recent survey of contingent faculty at USC found that on average, our professors are making $5,044² per course.

This means that a contingent faculty member teaching full time, or 6 classes per year, is making $30,264 annually.

Even worse, the vast majority of contingent faculty aren’t even offered full-time schedules, forcing them to work second and third jobs just to survive.

So how does that compare to spending on administrative positions? Let’s take a look:

As Laura McKenna points out, the income disparities between college faculty and administrators are “an important indication of a given higher-education institution’s fiscal priorities”. If we calculate the CEO-to-worker pay ratio at USC – in higher education this is a calculation of president-to-faculty pay – the numbers are striking.

President Nikias made more than $1.9 million in total compensation last year. That’s over 64 times as much as a contingent faculty member teaching a full load.

And it’s not just a few high earners. The average managerial salary at USC is $101,594 per year³. That’s over three times as much as a contingent faculty member teaching full-time.

For years, USC has embraced a business model of education that prioritizes administrative salaries over academic spending. In 2014 alone, the university spent upwards of $162 million on management4 – the 4th most of any institution in the country5.

It’s not just a boom in administrative bloat that should have us concerned, but also the rate at which administrative and executive compensation has outpaced spending on our university’s educators and investment in our core educational mission.

Tuition is more expensive than ever, but many of our faculty are struggling to make ends meet.

As USC prioritizes spending on lavish administrative and executive salaries over investment in student learning, it begs the question:

WTF are we paying for?

1. Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS). Title IV participating institutions: Public, 2 year and 4 year and above; Private, not-for-profit, 4 year and above; For-profit, 2 year and 4 year and above. Institution employees (excluding medical school)- all staff with faculty status that are Tenured, On Tenure Track or Not on Tenure Track/No Tenure System, Fall 2013 and Fall 2003. Contingent refers to all employees with faculty status Not on Tenure Track/Tenure System.

2. This is a calculation of the average part-time faculty pay across self-reported data in an SEIU Faculty Survey (Social Work; Cinematic Arts; Architecture; Public Policy), as well as faculty appointment letters (Letters, Arts, and Sciences; Art and Design; Social Work; Dramatic Arts; Public Policy). Average pay for reports of salary per hour was multiplied by 10 hours per week and 15weeks in a semester. Otherwise, appointment letters indicated pay per week, how many hours, and how many weeks designated per course. Pay per unit was then calculated as the total course pay divided by number of units per that course. Average per 1 unit pay was calculated, then multiplied by 3 to calculate the “Average Pay of Part-Time USC Faculty per 3-unit course.” For all faculty, the data was taken from the most current year or semester available.

3. National Center for Education Statistics IPEDS database: Total Management Outlays 2013-2014 school year for all Title IV receiving U.S. schools. Retrieved at http://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/datacenter/Default.aspx on 6/17/15.

4. National Center for Education Statistics IPEDS database: Total Management Outlays 2013-2014 school year for all Title IV receiving U.S. schools. Retrieved at http://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/datacenter/Default.aspxon 6/17/15.

5. National Center for Education Statistics IPEDS database: Total Management Outlays 2013-2014 school year for all Title IV receiving U.S. schools. Retrieved at http://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/datacenter/Default.aspxon 6/17/15.